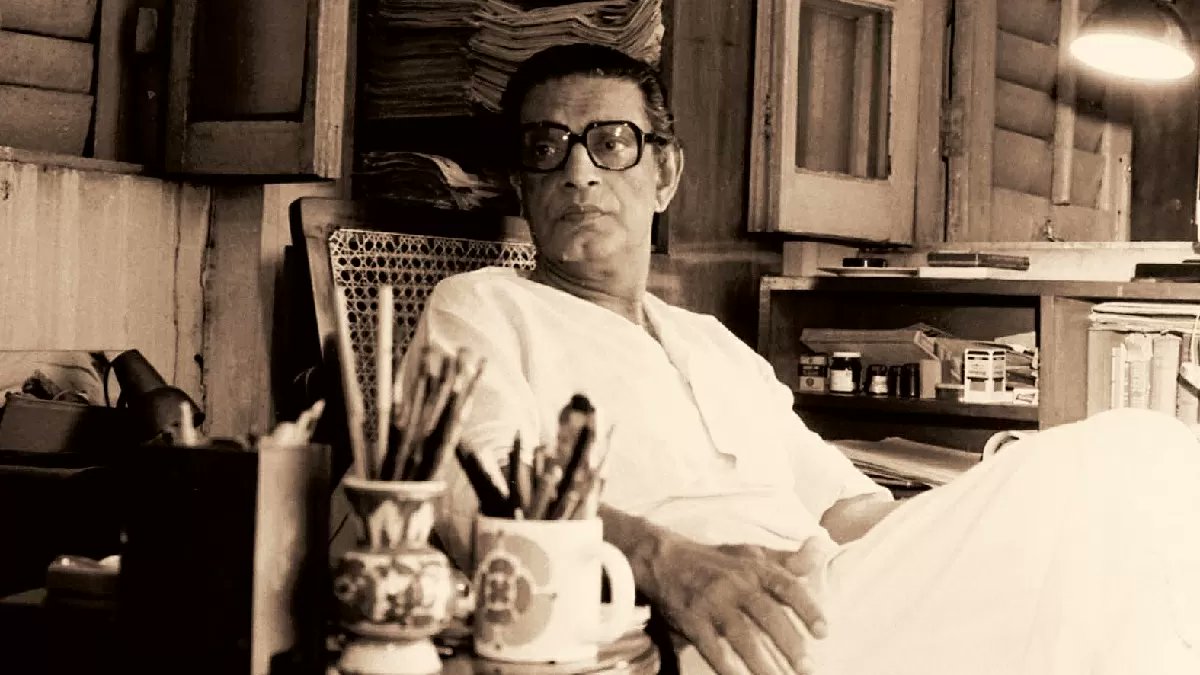

The name Satyajit Ray is inextricably linked with the golden age of Indian cinema. Widely regarded as one of the greatest auteurs in world cinema, Ray’s influence transcended national boundaries, setting a new benchmark for storytelling, realism, and artistry in film.

His works, most notably the Apu Trilogy, redefined Indian cinema, challenging conventions and elevating it to global platforms. But what if Satyajit Ray had never taken up filmmaking? What if Indian cinema had developed in his absence? This essay aims to explore the alternate trajectory of Indian cinema without the towering presence of Ray—what would have changed, what might have remained the same, and what could have emerged differently.

The State of Indian Cinema Before Ray

Before Ray’s directorial debut with Pather Panchali (1955), Indian cinema was largely dominated by mainstream Bollywood fare—musical dramas rich in fantasy, romance, and escapism. Filmmakers like V. Shantaram, Mehboob Khan, and Raj Kapoor were shaping the industry with socially conscious themes but packaged within a commercial format.

At the same time, South Indian cinema and Bengali cinema had their own distinct flavors, with directors like Bimal Roy bringing realism to the fore. However, it was Ray who firmly established the “parallel cinema” movement, offering a deeply humanistic, introspective, and poetic form of storytelling that eschewed melodrama for minimalism and realism.

Without Ray’s intervention, this nascent branch of Indian cinema might have either evolved differently or been stifled altogether.

The Lost Voice of Humanist Realism

Ray’s cinema was rooted in the everyday lives of ordinary people. Pather Panchali, Aparajito, and Apur Sansar explored poverty, resilience, coming of age, and the search for identity. In a world without Ray, this humanist approach to storytelling may have taken longer to find its footing in Indian cinema.

Directors like Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, and later Shyam Benegal and Govind Nihalani were part of the parallel cinema movement, but Ray’s global acclaim legitimized their work in the eyes of both Indian and international audiences. Without Ray to blaze the trail, the movement may have lacked the momentum and recognition necessary to flourish.

Without this influence, Indian cinema might have remained bifurcated: a commercial film industry pandering to the masses and a regional film culture with limited crossover appeal.

Impact on the International Reputation of Indian Cinema

Ray was the first Indian filmmaker to gain widespread recognition in the West. Pather Panchali won Best Human Document at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, placing Indian cinema firmly on the global map. Akira Kurosawa famously remarked, “Not to have seen the cinema of Satyajit Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.”

Without Ray, it is unlikely that Indian cinema would have achieved this level of early international prestige. Global film festivals might have continued to view Indian films as melodramatic and exotic rather than nuanced and sophisticated. This could have stifled cross-cultural collaborations, funding for independent films, and the entry of Indian cinema into world cinema discourses.

India might have remained a cinematic outlier rather than a respected participant in the global film community.

The Fate of Regional Cinema

Ray’s legacy is closely tied to Bengali cinema, which flourished under his influence. His works proved that regional language films could achieve both artistic excellence and international acclaim. In his absence, Bengali cinema might have remained more parochial and less daring in its ambitions.

Moreover, Ray’s success inspired filmmakers in other regional industries, such as Malayalam and Marathi cinema, to explore minimalist and meaningful narratives. The entire ecology of Indian regional cinema could have evolved along a more commercial or formulaic line had Ray not provided a model for balancing artistry with cultural specificity.

Technological and Narrative Innovation

Ray was a pioneer not only in storytelling but also in the technical aspects of filmmaking. He designed his own typefaces, composed music, storyboarded meticulously, and even operated the camera on occasion. His technical versatility became a model for future Indian filmmakers working with limited resources.

In his absence, Indian filmmakers may not have been as inspired to pursue such craftsmanship. The development of cinematic language in India—especially regarding visual economy, sound design, and narrative pacing—might have lagged behind.

Ray’s use of natural light, real locations, non-professional actors, and ambient sound was revolutionary. It showed that filmmaking didn’t require grand sets and budgets, but a sensitive eye and deep commitment to truth. Without him, Indian cinema might have continued over-relying on theatricality and studio-bound conventions.

Literary Adaptations and Intellectual Cinema

Ray, a writer himself, adapted works by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Rabindranath Tagore, and others with depth and sensitivity. His success demonstrated that cinema could engage deeply with literature, fostering a tradition of adaptations that respected source material and raised cinematic literacy.

Without him, it is uncertain whether such a strong literary-cinematic link would have been forged. The space for “intellectual cinema” in India—one that engaged with philosophical, psychological, and cultural themes—might have been considerably narrower.

Furthermore, Ray’s own writings, essays, and interviews have educated generations of filmmakers, serving as a curriculum in film theory, practice, and ethics. That intellectual legacy would be conspicuously absent.

The Growth of Parallel Cinema: A Delayed or Derailed Movement

The Indian New Wave, or Parallel Cinema, reached its height in the 1970s and 1980s with directors like Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, and K. Hariharan creating challenging and avant-garde films. Many of them cited Ray as an inspiration or at least as a benchmark of quality.

Without Ray, it’s conceivable that this movement might have failed to secure the funding, institutional support, or audience curiosity necessary to sustain itself. Film societies, national awards, and government funding initiatives that supported these filmmakers often did so on the credibility Ray had already built.

The cultural appetite for such films may have been dulled or postponed, with mainstream cinema tightening its grip further.

Ripple Effects on Contemporary Indian Filmmakers

Even today, directors like Anurag Kashyap, Ritesh Batra, Dibakar Banerjee, and Chaitanya Tamhane acknowledge the influence of Ray, whether directly or indirectly. His emphasis on mood, subtlety, and realism has seeped into the DNA of Indian independent cinema.

Without Ray, the evolution of this indie wave might have taken a different route, possibly borrowing more from Western auteurs than developing a homegrown narrative identity. The loss wouldn’t just be of a filmmaker but of an entire philosophical and aesthetic lineage.

The Absence of a Cultural Icon

Ray was not only a filmmaker but a cultural institution. He was also an illustrator, graphic designer, composer, and writer of detective fiction (Feluda) and science fiction. His contributions to children’s literature and popular culture are immense.

Without him, India would have lost one of its true Renaissance figures—someone who influenced not just cinema but art, music, literature, and education. His multidisciplinary legacy shaped how generations approached creativity, ethics, and cultural identity.

The absence of such a figure would leave a void not easily filled by a single successor, and the holistic enrichment of Indian culture would be significantly diminished.

Alternate Possibilities: Who Might Have Filled the Gap?

Had Ray never emerged, could someone else have taken his place? Perhaps Ritwik Ghatak or Mrinal Sen might have carried the mantle, but their styles were more radical and less accessible. Ghatak’s raw emotionalism and Sen’s political critiques lacked the lyrical humanism of Ray’s narratives.

In South India, Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Girish Kasaravalli emerged later, and while brilliant, may have remained regionally confined without the gateway Ray had unlocked.

Internationally, Ray’s absence might have created space for directors like Mira Nair or Shekhar Kapur to rise earlier, but it’s unlikely they could have originated the kind of indigenous cinematic grammar Ray pioneered.

The absence of Satyajit Ray from the annals of Indian cinema would not simply represent the loss of a single filmmaker but the redirection of an entire cinematic and cultural ethos. His presence validated a form of filmmaking that prized depth over spectacle, realism over fantasy, and humanity over hyperbole.

Without Ray, Indian cinema might have remained creatively lopsided—dominated by spectacle and lacking a credible, respected alternative. The international community might have taken longer to appreciate the depth of Indian storytelling, and a generation of filmmakers might never have found their voices. Indian cinema without Satyajit Ray is like imagining a novel without prose—it may exist, but it would be missing its soul.